Free International Writing Competition

ORIGINS

Results

OVERALL WINNER

North East Lass

Kathy Hoyle

Coventry, West Midlands

Category Winners

Non-Fiction: North East Lass, Kathy Hoyle, Coventry, West Midlands

Poetry: Ma Mer Maman, Paris Rosemont, Sydney, Australia

Short Story: Calling Sabrina, Jean Cooper-Moran, Newnham, Gloucestershire

NON FICTION RESULTS

1st Place: North East Lass, Kathy Hoyle, Coventry, West Midlands

2nd Place: Ma Clar The Village Santiwah, Noel Otancia, Chaguanas, Trinidad and Tobago

3rd Place: La Bella Luna, Kate Durrant, Cork, Ireland

POETRY RESULTS

1st Place: Ma Mer Maman, Paris Rosemont, Sydney, Australia

2nd Place: A Monster Born In My Brain, Tagayan Janrhesam, Zamboanga City, Philippines

3rd Place: The Lough, Michael Coleman, Belfast, Northern Ireland

SHORT STORY RESULTS

1st Place: Calling Sabrina, Jean Cooper-Moran, Newnham, Gloucestershire

2nd Place: A Sense of Duty, Chris Cottom, Macclesfield, Cheshire

3rd Place: Black Gold, Jeff Taylor, Hamilton New Zealand

SHORTLIST BY CATEGORY

POETRY SHORTLIST:

A Monster Born in My Brain - by Tagayan Janrhesam from Zamboanga City in the Philippines

Global Gallery – by Megan Easley-Walsh from Kildare in Ireland.

Ma Mer Maman - by Paris Rosemont from Sydney, Australia.

Jazz in the Cathedral – by Joy Heath from Waltham, North East Lincolnshire

The Lough - by Michael Coleman from Belfast in Northern Ireland

SHORT STORY SHORTLIST:

Who We Are - by Hank Isaac from Ocean Shores, United States.

Calling Sabrina - by Jean Cooper-Moran from Newnham in Gloucestershire

Black Gold – by Jeff Taylor from Hamilton, New Zealand.

A Sense of Duty - by Chris Cottom from Macclesfield in Cheshire

NON FICTION SHORTLIST:

'What's In A Name'? – by Peter Barrett from Wootton, North Lincolnshire

La Bella Luna - by Kate Durrant in Cork, Ireland.

Ma Clar The Village Santiwah - by Noel Otancia from Chaguanas, Trinidad and Tobago.

North East Lass - by Kathy Hoyle from Coventry.

WINNING ENTRIES

North-East Lass

I am rock pool, a cliff edge, a marram grass clump, an oyster catcher, wading, a guillemot diving beneath bleak black waves. I am sea coal and sand, a dropped H, a sea-tang lilt, a washing day song drifting over a back-alley wall.

I am the daughter of a mam. A seamstress, a maker of clothes, a maker of money from an empty purse, a make-ends-meet, a meat pie maker on Sundays, fresh flour on rolling pin hands.

I am the daughter of a dad. A miner, a fisherman, a mechanical fitter, job after job, chasing the crumbling landscape, coal and brine and oil and whiskers that tickle, a heavy black coat, a codling reel with a feathered weight and the weight of the world carried on an aching back.

I am seagull shit and a slug of cider in a wind-swept bus shelter, a first kiss on a rusting pier, vinegar lips from scrannin’ fish and chips, vinegar-mouthed swearing on girl’s nights out, strutting in short skirts, cackling through the doors of a working man’s club for the pound a pint and to watch the turn. I am terns and whelks and cockles and brown-eyed seals that bask on salt flats watching the factory smoke plume.

I am fish guts and fish hooks, a fish hooked to a small town harbour where cleats clang on freezing winter days.

I am breath-held, with a ten pound note tucked into a rucksack, travelling on a coach bound for the South. I am a don’t look back, a lighthouse beam following dreams, to cities filled with empty faces. I am a phone call home, I’m fine, I’m fine, a tear-soaked duvet, a snivellin’ bairn.

I am carved of stone, rebuilt, replaced, an accent buried, a wanderer, a traveller, a tea maker, a nurse. I am wings, a smile, a travel the world. I am first class, working class, an oh-so-friendly north-east lass.

I am a visit home, a diagnosis, a walk on the pier, a storm brewing, sea fret, tears falling onto mossed rocks, a heart cracked wide open.

I am a mother. A mother without a mother, alone and lost. I am a workhorse, a maker of clothes, a maker of money from an empty purse, a make-ends-meet, a job after job, chasing my own tail, the weight of the world on my aching back, yet always grateful for the lessons learnt.

I am North Sea deep and blue sky wide.

I am all the things you know I am, The X Factor, bingo, benefits and Asda, a broken-wheeled buggy, with a hand-me down kid.

And I am all the things you will never know, Descartes, Debussy, Degas, a bibliophile, a scholar, a dreamer, a role model, a vast curve, a sharp edge, a sea hag, a heart, a soul.

I am always running, with the wind skimming through my sea-kelp hair, searching, searching for a way back home.

Ma Mer Maman

I find myself

here again

to her indecipherable whispers

I come here

I nestle into the Oedipal womb of my longing

as she strokes my hair, silken as seaweed

singing lullabies:

Ma Mer, Maman

by the foaming mouth of the sea, listening

shhhh..... shhhh.....

in times of distress

more than my cold birth mother ever could

it’s going to be okay

she comforts me

hush, hush my darling—

come suckle in the wet of our mutual wanting and I shall cradle you till my bed runs dry

Calling Sabrina

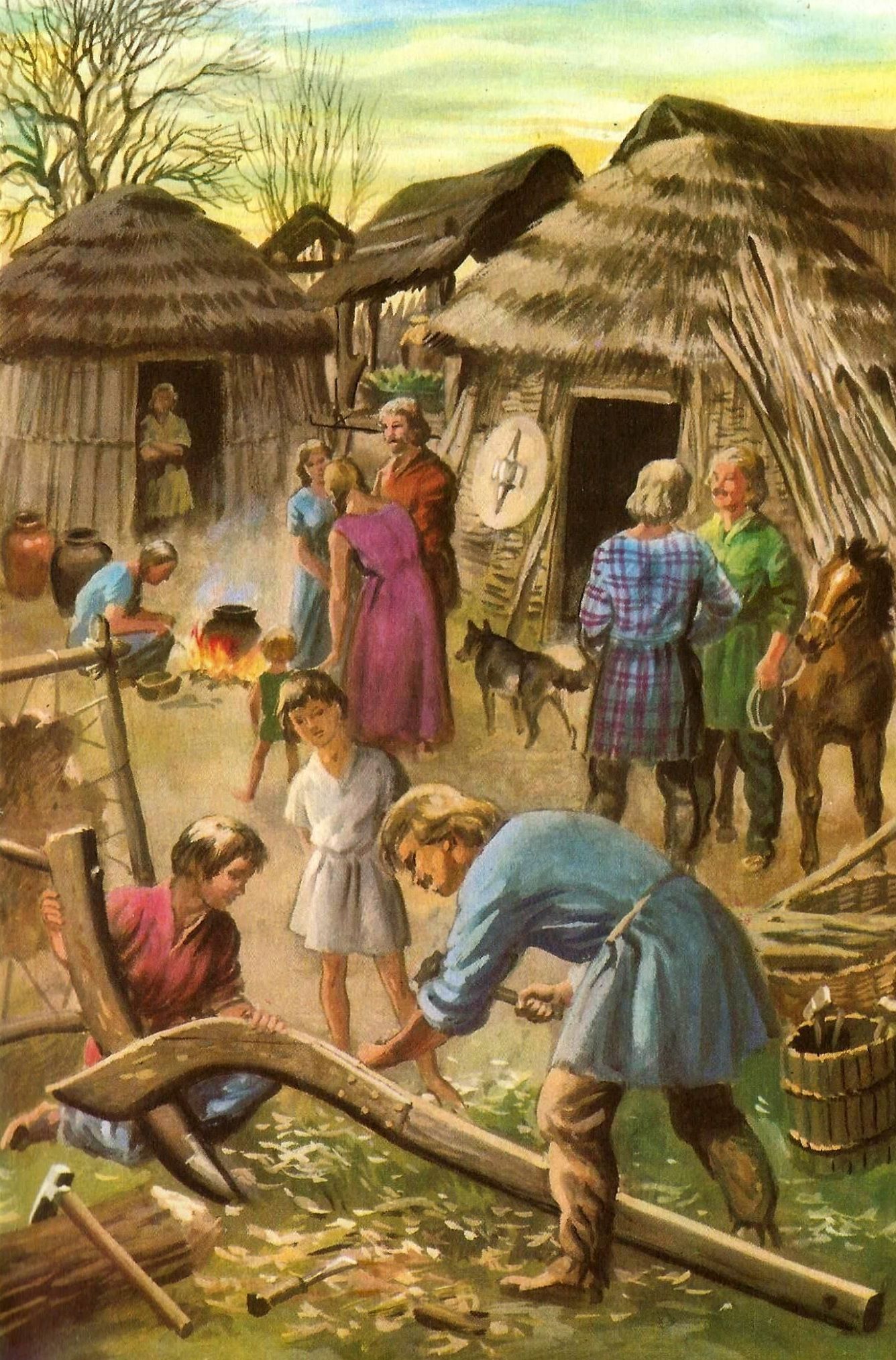

I love this part of the day; no-one else is around. In the silvery light of dawn, I see to the edge of the world over the black shapes of waving tops of wart-cups, tall, thin- stemmed wyds, and spiky, needle-tipped brochs. Curling smoke rises from the hearths of our Ordovici neighbours to the north: farms upon farms in small clusters all the way to high, blue mountains wreathed in silken clouds. Westward are the shadowy, dark slopes of the Demetae’s hunting country, and beyond that, to the western sea, are the island homes of our teachers and judges, the druids. We, the Siluriae, live in our Forest.

I am looking out for a group coming to our farms; Father said last night there’s news of a great leader coming to help us push back the invaders. The Roman Second Augustan Legion has arrived, meaning that our people are threatened again by invasion from across the river. That is why the clans are meeting the famous men to hear their battle plan. I give my wartcup a pat, and slide downwards, my bare feet finding the well-used grips as I swing through the arms, drop to the ground and head for home.

An hour later, we wait in the gathering field where a huge crowd is welcoming famous warrior Caradoc, prince of the eastern tribe, the Catuvellauni. His escort is on horseback and dressed for battle already, hair braided and painted, pulled up and back so that the cone-shaped helmets fit securely. Their leather and woollen tunics, trousers and iron breastplates are almost invisible under huge, woven cloaks patterned in red and blue squares, floating in the breeze like war banners.

Caradoc wears a wide, finely-worked band of gold around his neck. It gleams and glitters, drawing our eyes. He’s painted for war, dark eyes ringed with blue symbols, the white spears of Sabrina drawn on the hard planes of his face. Women coo like doves all around me. He looks like a prince, making me proud he has come to our Silurian villages to plan the attack. A man rides forward from the rear of the group. He draws all eyes too but for a different reason. Unlike Caradoc he’s wearing nothing on his head but a silver band around his brow. Black hair falls freely to his shoulders, and he is shaved unlike the warriors. Although he is dressed like the others, the blackened, toughened ox hide cape mantling his shoulders tells the whole story. This is a druid going to war: he sits as still as air before a thunderstorm. Father nods to Caradoc who faces the hushed crowd to speak to us.

‘We have the chance to stop the advance of the Romans and we need your help, all of you. They’re across the river, ready to move camp. But they must cross the river at a certain time, Tarel says. We must give them a reason to move just at that time.’

People call out, not really understanding. Caradoc re-mounts and raises his hand.

‘It’s true; we need to lure them across the river to face us, and trust to our gods Sabrina and Ocelus for what follows. Tarel from the college is here.’

The druid raises his hand, and I swear a light breeze carrying summer-scents flows around us. The prince leans forward, throwing his voice across our upturned faces.

‘He will make calculations for us. We need all of you there on the bank, shouting, singing, dancing, shaking whatever weapons you’ve got to hand. Yes, women and children too, as many voices as we can raise.’

I feel excitement mounting, watching the prince’s words light fires in this host of people from as far away as a crow can fly in a day. He wants us to move to the river, to a place called the ‘Noose’. That’s a huge channel as wide as three fields, a treacherous place for fishing even when the Romans aren’t there. At a low tide your coracle can get caught on the sandbank that rises in the middle of the river. You will sink into the sand and die. Tarel confers with Father and Caradoc, who gives the signal to go forward. When we arrive at the beach, we taunt the Romans on the opposite bank. It is clear what they mean to do, but we want them to do it now, at the time Tarel says river goddess Sabrina will come to our aid. We sing, ‘Romans, go away. Fly, little birds. Nowhere to roost here.’

Other people say things that are a lot ruder. Some, who know the Roman’s language, insult their emperor, and their legions. We all dance around, shaking whatever is to hand: a bright, hectic cloud of protestors. Tarel calls out to Sabrina, his voice so deep and strong that it resounds up and down the river. Finally losing his temper, the Roman commander sends their foot soldiers and cavalry, heavily clad in iron, across the small channel of the eastern bank. They reach the far side of the Noose sands. I am a little scared now. Sunlight sparks off their iron plating, and their faces are grim as nightmares. But Tarel keeps chanting.

We wait, still yelling and singing, until Sabrina works a miracle. Horrified soldiers on the sandbank watch the river sweeping up the western channel in a flood tide. There’s confusion as they cannot go any further. Trying to retreat across the sands, men and horses plunge around in a muddle. When some of them reach the eastern side, they are cut off by the tide flowing down and around the Noose to meet the flood tide still moving up the eastern channel, a barrier so formidable it must be magical.

Most soldiers die, sucked down into the sand. I am sorry about the horses, but as Father says, this is how we fight for what is ours in the Forest: our lands, our homes, and our people.

Made possible with support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund with thanks to National Lottery players

Sponsored by

Part of the Grimsby Heritage Project lead by The Equality Practice

Get in touch

Championing creative talent.

Serving the community.

Useful Links

All Rights Reserved | Hammond House Ltd | Privacy Policy